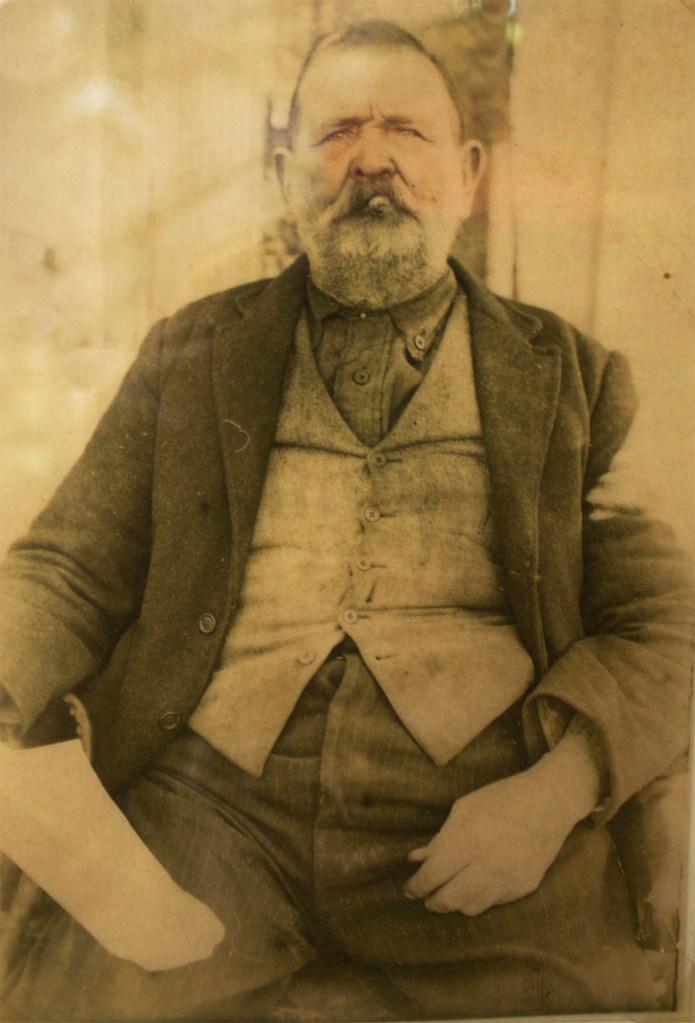

Gulgong 1928 – The man who triggered “the last of the poor man’s gold rushes’’ in New South Wales, died an invalid pensioner at the ripe old age of 80.

John Thomas Saunders Junior passed away in 1928 after a short stay in the hospital of the town which sprang up overnight around his famous find.

Those who visit the town now cannot ignore its golden history – it is reflected in its very streets, with gold-rush era style buildings and tourist experiences abounding.

And Saunders, dubbed the ‘grand old man of Gulgong’, is also written into this history. One of the town’s tourist attraction, the Gulgong Gold Experience, is on his own street – Tom Saunders Avenue.

But Saunder’s headstone, in the sprawling Gulgong cemetry, however, does little to portray the importance of the man to the town, which surged from an “uninteresting little hamlet” to a bustling region overrun by gold-hungry men and hotels to quench their thirsts.

Tom, as he was known, was the youngest of a tribe of at least 10 Saunders children. He was born by the Hawkesbury River in 1848, and grew up breathing gold dust – by the age of six, his family was living on the famous Ophir gold diggings, where Australia’s first payable gold was found in 1851.

A Mudgee newspaper article published on his death described his early prospecting as he played in the dirt of the goldfield.

“There the youngster, a baby-gold-getter, washed his first prospect in his mother’s baking dish and won for himself the values that incited him to pursue the elusive profit.

“The spirit of the chase was bred in him.

MUDGEE GUARDIAN

The same article describes Tom as becoming a prospector at the age of 12.

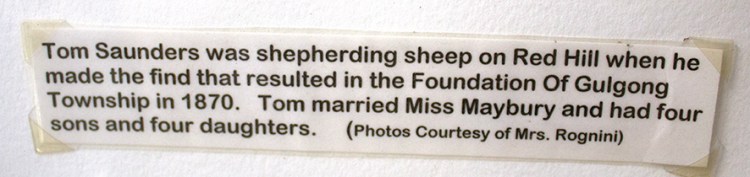

He was among the first rushers at Biragambul, less than 10 kilometres from the scene of his later fame. The next ten years were spent following that golden lure. But when he was about 22, he hit major paydirt.

As so often happens with history, the truth is quite slippery.

Multiple internet searches refer to Tom as a shepherd. Whether he was or not is difficult to ascertain. Some newspaper articles mention that he was working for a station owner, but that does not mean he spent his days herding sheep.

Also, in goldfields parlance of the time the term referred to the class of bush workers who ignited the gold rush – ordinary people, not trained geologists. The term was also used in a derogatory fashion to denote someone who followed or watched other miners, trying to round up some of their success.

Furthermore, one common story about Saunder’s discovery is that an elderly shepherd did indeed find some promising quartz samples 11 years beforehand, and they were kept by the Saunders family until Tom Jr decided to investigate further.

A letter to the editor in the Gulgong Guardian by someone calling themselves “Jumbuck” names that shepherd as Irvine, and claims Irvine showed Tom the region one wet day when there were “no sheep fit to shear’’.

Another story says that Saunders was using a plan “in the possession of his father’’, on which he based his prospecting. The truth may be a combination of the two.

Either way, Gulgong was known to be auriferous (what a wonderful word), with solid specimens known many years before the rush occurred. It was referred to as a poor man’s rush because the gold was close to the surface, with steady returns for a man working without expensive machinery.

One story claims Tom “struck his patch’’ in January 1970, when he supposedly washed 1lb of gold in a fortnight.

“This was good enough and he reported the find to the warden at Mudgee.”

A little rush followed but the lack of water meant diggers abandoned their efforts. Tom is said to have persisted, and in April made the find that, along with a couple of handy thunderstorms filling the creeks, started the rush that put Gulgong on the map.

At the time there was talk of a reward for the find, and conjecture about whether it should go to Saunders, his prospecting friend Joseph Dietz or even the shepherd Irvine.

Mr Jumbuck, in the Gulgong Guardian, claimed that the

shepherd Irvine is entitled to at least an equal share of the honour and profit of the discovery of Gulgong with Mr Saunders…more so than Saunder’s mate Mr Deitz who was not with Mr. Saunders when he found the gold.

mudgee guardian

There is no proof a reward was ever given. A cairn was erected at Red Hill Reserve in 1970, on the centenary of the find. It partially reads “As An Acknowledgement Of The Worth Of Thomas Saunders Discovery And A Tribute To The Pioneering Spirit Of The Goldminers Whose Work And Initiative Established This Town Of Gulgong.”

Tom spent much of the rest of his life centred around Gulgong, marrying in 1872 and fathering eight children.

Tom was a contemporary of Australian author Henry Lawson – there is a photograph on the Online History of Gulgung and surrounding areas website featuring the two side-by-side.

Sources: Australian Town and Country Journal, Saturday 11 June 1898, p24

Empire, Saturday 25 November 1871, page 4A

Mudgee Guardian and North-Western Representative, Monday, September 21, 1953 , p3 Thursday 5 March 1953 – p 10

Gulgong Guardian, Issue No 106, 21 August 1872

History – Gulgong NSW at https://gulgong.com.au/see-historical-gulgong/history/

Gulgong gold experience at https://www.gulgonggold.com.au/

No AI assistance was used in the production of this article.